Social dimension of mining

Overview and context

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) refers to mining by individuals, groups, families or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanisation, often in the informal sector of the market (Hentschel et al. 2002). The ASM sector is usually high labour intensive and requires low investment levels. Compared to the Large Scale Mining (LSM), the demand for land is usually lower, due to the small concessions areas, and legal status is mostly informal on the production site.

According to recent estimates provided by the Delve platform, more than 40 million people worldwide were directly engaged in ASM in 2019, 30% of which being women. In Africa, the share of women is about 40-50%, in Asia less than 10% and in Latin America between 10 and 20% (IGF 2017). Women are usually not involved in digging and other heavy mining activities, but participate in various activities like ore processing and sale and provision of food to the miners (IGF 2017).

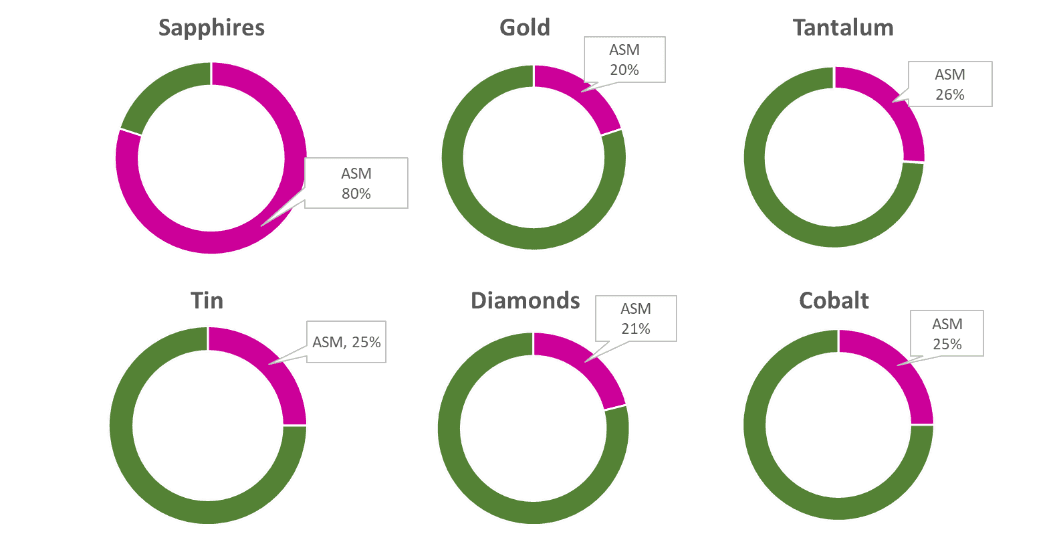

According to very rough estimates, artisanal and small-scale mining produces around 15-20% of global minerals, including 80% of all sapphires, 20% of all gold, and 20% of diamonds (IGF 2017). ASM is also a major producer of raw materials strategic to electronics manufacturing, and accounts for 26% of global tantalum production and 25% of tin production (IGF 2017) (figure 1).

Main features of ASM

The sector is very heterogeneous in terms of scale, legality, demographics and seasonality. Operations exploit marginal and small deposits, are labour intensive and have poor access to markets and support services. Being informal and unregulated, much ASM activity operates outside of health, safety and environmental legislation or standards. In some cases, artisanal miners are controlled by armed groups and the resources extracted in this contexts are then financing conflicts and insurrections. Conflicts with LSM operators due to land disputes and access to resources can also occur. In cases where ASM and Large Scale Mining (LSM) operate in the same or neighbouring concessions, clashes over land disputes and access to resources are significant.

ASM sector can also have positive impacts in local communities when it receives adequate support and fair access to markets. Many authors agree on the benefits arising from the formalization of the ASM, which would also drive an improvement of working conditions and a reduction of environmental impacts. This is also acknowledged in a recent UN IRP report on Minerals Resource Governance, which urges the private sector and other stakeholders to implement transparent practices across the supply chains and support ASM integration into local, national, regional and international supply chains.

According to Hilson&Maconachie (2020), the formalization of the ASM sector could contribute to several the Sustainable Development Goals, by means of, for instance:

- Job creation and poverty alleviation

- Empowerment of women

- Improved transparency in the the supply chain

Some responsible sourcing initiatives for improving the conditions of artisanal mining have been implemented in recent years. For instance Fairtrade gold, Planet Gold, Fairmined (for gold) and in the case of cobalt, Better Mining and Mutoshi Pilot Project.

The impact of the above-mentioned initiatives on cobalt ASM has been analysed in the JRC study “Responsible and sustainable sourcing of batteries raw materials”.

Overview and context

Stimulating investment for the purpose of job creation is one of the Juncker Commission's priorities. Increasing labour productivity, reducing the unemployment rate and promoting decent work is also an objective in the United Nations (UN) SDGs.

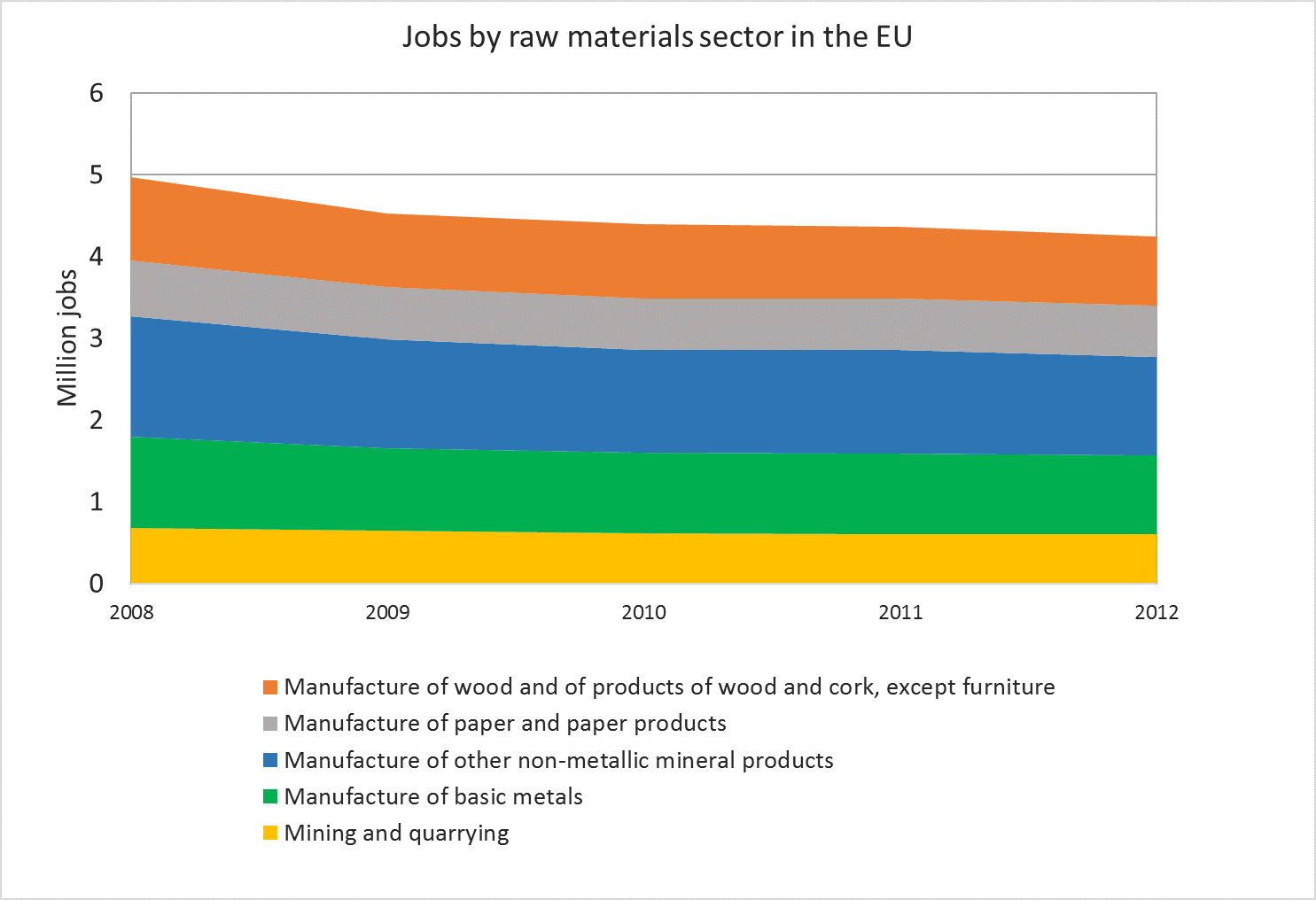

Raw materials play a fundamental role in the creation of employment. In 2014, the economic activities relating to biotic and abiotic raw materials production employed more than 4.4 million people[1]. Moreover, the waste management and recycling sectors also contribute significantly to employment. According to estimates from various sources, 3.4 million jobs have been created by circular economy-related activities in the EU[2].

The contribution of the raw materials sector to EU employment goes far beyond economic activities strictly related to the production of materials. Downstream in the supply chain, the number of jobs created in the manufacture of semi-finished products is a lot higher than the number of jobs from materials production alone. For instance, while the EU sector of metal mining employs around 16000 persons, the downstream manufacturing of metals creates almost 12 million jobs[3].

Worldwide, the raw materials sectors (especially mining and forestry) are characterised by a high degree of informality, particularly in developing countries. For instance, the global mining industry employs around 2.5 million people, while, according to estimates, informal mining activities provide jobs for 15–20 million people[4]. In the forestry sector, informal work in the sector is fostered by the expansion of illegal logging.

Decent work

As for other sectors, raw materials industries also face challenges related to the achievement of ‘decent work’. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), ‘decent work sums up the aspirations of people in their working lives. It involves opportunities for work that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.’

Especially in developing countries, occupational hazards, work accidents and child labour particularly affect the mining sector. According to the ILO, more than one million children work as miners worldwide. They are almost exclusively found in artisanal small-scale mining operations in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In addition, in developing countries, the recovery of materials from waste (and especially e-waste) is mainly carried out by thousands of individual workers and children within the informal sector.

Child labour

The definition of child labour is derived from the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, ILO Conventions No 138, and No 182 and the Ghana Children’s Act 1998 (Act 560). It refers to all work that is harmful and hazardous to a child’s health, safety and development, taking into account the age of the child, the conditions under which the work takes place and the time at which the work is done. The worst forms of child labour are defined by ILO Convention No 182 to include all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery.

In order to combat child labour, the ILO’s International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) was created in 1992, aimed at strengthening the capacity of countries to deal with the problem and promoting a worldwide movement.

While the number of children working in mining is much lower than the number occupied in agriculture, the nature of this work is considered extremely dangerous to children because of the heavy loads, the strenuous work, the unstable underground structures, heavy tools and equipment, the toxic and often explosive chemicals, and the exposure to extremes of heat and cold. For this reason, in 2006, the ILO promoted the programme ‘Minors out of Mining’[5], aiming at eliminating child labour in small-scale mining, starting with countries where the problem is most serious.

Migration

Worldwide, the mining industry is also characterised by the significant presence of foreign migrant workers. While there is lack of information concerning the migrant flows in the mining industry, a report from the IL[6] describes, in six national case studies, a very diversified picture. Indeed, the migration of low-skilled and of skilled labour have very different features. Skilled labour is usually regulated, including with regard to legal migratory status. Working conditions usually vary in large-scale compared with small-scale mining, as well as in developing compared with developed countries. In general, temporary low-skilled migrant workers are often more vulnerable to the risk of employer exploitation and are not always paid at current market rates for the work.

Gender balance

While raw materials industries are usually portrayed as male-dominated activities, attention has been given to the feminisation of the mining sector. This is especially the case in ASM, where the number of women engaged in mining as a means of livelihood is increasing[7]. A number of initiatives from civil society and industry, as well as policy processes and research programmes with LSM corporations, are currently under way.

Facts and Figures

Figure 3 Number of jobs for a selection of raw materials economic sectors in the EU (2008-2012) Source: EC - European Commission. Raw materials scoreboard European Innovation Partnership on raw materials. Luxembourg; 2016.

[1] Source: EUROSTAT

[2] Source: WRAP (2015) Economic Growth Potential of More Circular Economies

[3] EC - European Commission. Raw materials Scoreboard. European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials. Luxembourg; 2016.

[4] Raw Materials Group and International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). 2014. The role of mining in national economies, 2nd ed., 6

[5] http://www.ilo.org/ipec/areas/Miningandquarrying/WCMS_163749/lang--en/index.htm

[6] http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_538488.pdf

[7] Lahiri-Dutt, K. 2015. “The feminization of Mining” in Geography Compass, vol. 9, No.9, 523-541

Overview and context

Resource Governance is defined as “the manner in which power is exercised and policies are made in the management of a country's oil, gas and mineral resources for development.” (Natural Resource Governance Glossary). According to the International Council of Metals and Mining (ICMM), good governance is based on transparency and accountability. This is acknowledged in the first of the ICMM Mining Principles, which serve as best-practice framework for sustainable development in the mining and metals industry.

A new report of the UN International Resource Panel on Mineral Resource Governance stresses the importance of good governance for mitigating the adverse impacts and enhancing the positive economic, social and environmental outcomes of mining. It also proposes the framework of ‘Sustainable Development Licence to Operate’ (SDLO) to improve the net societal benefits of mining, addressing the nexus of all environmental, social and economic concerns included in the Sustainable Development Goals. The framework is designed to involve all actors in the extractive sector across the public, private and civil society sectors.

CC: Rafal Olechowski

Responsible business conduct

At corporate level, good governance implies the application of ethical business practices, the disclosure of information, the prevention of bribery and corruption and the contribution to sustainable development. The OECD published guidelines for responsible business conduct to multinational enterprises and guidance on how to conduct due diligence, including sector-specific reports including those on responsible minerals supply chains.

Integrity refers mainly to ethical and lawful behaviour, including systems and processes through which an individual or organization can report concerns about illegal, irregular, dangerous or unethical practices related to the organization’s operations.

According to the OECD, corruption has become increasingly complex and sophisticated, affecting each stage of the extractive value chain with potential huge revenue losses for the public coffers. The different corruption risk typologies in the extractive sector and related mitigation measures are described in a dedicated report (OECD, 2016).

Management of natural resources

At country level, resource governance concerns the management of a country natural resources endowment for the benefit of the whole society. It is widely acknowledged that poor governance in some countries is one of the causes for the so-called “resource curse”, a phenomenon by which countries rich in natural resources (“resource-rich” countries) tend to have less economic growth, worse development outcomes, higher inequality and weaker institutions than countries with fewer natural resources.

Governance deficits foster the arise of conflicts for the access to resources. In the case of conflict minerals, profits of resource extraction and illicit trade finance civil wars and conflicts.

The role of good governance and institutions has proved to be decisive in avoiding resource curse and promoting sustainable development and prosperity. Examples of countries benefiting from resource extraction are, for instance, Australia, Canada, Norway and Botswana (UNEP IRP 2020).

Resource governance initiatives

Several initiatives and tools to measure and improve the natural resource governance exist, e.g.:

- The Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) is a not-for-profit organization carrying out analysis and applied research for supporting improvement of resource governance. Examples of tools developed by NRGI are the Resource Governance Index, which measures the quality of governance in the oil, gas and mining sectors of 58 countries and the Natural Resource Charter, a set of principles to guide governments' and societies' use of natural resources so these economic opportunities result in maximum and sustained returns for a country's citizens.

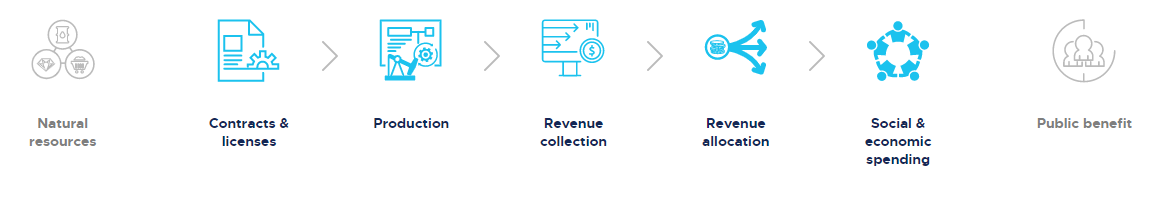

- The Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a global standard for improving transparency and governance along the value chain. It takes into account all the steps from the legal framework, distribution of licenses and contracts, exploration and production phase, revenue collection; revenue allocation and social and economic spending. EITI is formed by a coalition of governments, companies, civil society groups, investors and international organizations.

Figure 1: Steps where information disclosure is required under the EITI standard (Source: screenshot from https://eiti.org/, accessed on May 2020)

- Publish What you Pay is an international campaign claiming transparency and accountability in the extractive sector, in order to ensure that population in resource-rich countries can benefit from the mining revenues, preventing the risk of conflicts and resource curse.

- The Fraser Institute, a Canadian public policy think-tank, performs annual mining surveys, which mirrors the opinion of managers and executives of senior and junior companies within the mining jurisdictions and on those policy factors with which they are familiar. The Policy Perception Index (PPI) measures the opinion about the effects of government policy on attitudes towards exploration investment in mining jurisdictions.

A broader overview of initiatives on governance in the raw materials sectors can be found in the session “International Initiatives”.

Good governance in EU countries

Beyond the above presented principles and international initiatives which EU countries shall be compliant in line with the relevant pieces of Community legislation and policies, the Member States permitting regimes are also core elements of good governance and of the EU raw materials policy. RMIS has rich information on this aspect elsewhere, and the RMIS workshops frequently address this context of governance in details. (Hamor et al. 2019).

What concerns the global comparison of the efficiency of mineral policies, and the public acceptance issues, the EU Raw Materials Scoreboard provides indicators for the monitoring of these elements of governance.

Overview and context

Occupational safety and health (OSH) at work is important in the context of social sustainability in any economic sector. With respect to the raw materials industry, a safe and healthy working environment is an important indicator of the level of acceptance or approval of an industry and its operations by local communities and stakeholders. OSH is also essential for a productive and competitive economy (COM(2014) 332).

OSH constitutes one of the areas where strict safety standards exist and where EU policies have had a large impact in recent years. Significant decreases have been achieved in virtually all economic sectors in both the number of workplace accidents and the overall incidence rate (i.e. the number of accidents relative to the number of people employed in a sector) (EC, 2008).

In the raw materials sector, specific hazards include the exposure of employees to chemicals, noise and high temperatures. Proper management of work-related risks and hazards helps to minimise employees’ exposure to risk factors. Sound risk management may include employing operators with adequate skills and levels of expertise, having the proper protective equipment and establishing risk management systems at the production site.

International initiatives and legislation on occupational safety and health

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework recognises that OSH is a vital component of decent work. Accordingly, target 8.8 aims to protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers. The indicators used to monitor this target focus on the frequency rates of fatal and non-fatal occupational injuries and the increase in national compliance of labour rights based on ILO sources and national legislation.

The mining sector has been reviewed during the 19th session of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development. In this context, the improvement of workers' health and safety is considered a priority area for maximising the sustainability of the sector.

The Convention of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) on Safety and Health in Mines (1995, No. 176) regulates the various aspects of safety and health characteristics for work in mines, including inspection, special working devices and special protective equipment for workers. It also prescribes requirements relating to mine rescue.

Because of the presence of hazards, OSH also remains a challenge in the metal production sector, where the ILO is developing codes of practice for the iron and steel industry and for the non-ferrous metals sectors, assisting all those involved in these industries to improve safety and health records.

At EU level, Article 153 of the TFEU gives the EU the authority to adopt directives in the field of safety and health at work.

Current EU policy is outlined in the EU Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Strategic Framework 2014-2020 (COM/2014/0332 final). This policy is built on the OSH Framework Directive (89/391) and has a wide scope and is complemented by further directives focusing on specific aspects of safety and health at work.

The Framework Directive (89/391) encourages improvements in the safety and health of workers at work and introduced the obligation for employers to keep a list of occupational accidents resulting in a worker being unfit for work for more than three days, and, in accordance with national laws and/or practices, to draw up reports on occupational accidents suffered by their workers.

On this basis, the European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW) project was launched in 1990 to harmonise data on accidents at work for all accidents resulting in more than three days’ absence from work. In 2001, the report ‘European Statistics on Accidents at Work - Methodology’, was published by Eurostat and DG Employment and social affairs, setting out work on methodology since 1990.

Concerning the extractive industries, Directive 92/91/EEC concerns the protection of workers in the mineral-extracting industries through drilling, whileDirective 92/104/EEC sets the minimum requirements for improving the safety and health protection of workers in surface and underground mineral-extracting industries. Directive 94/9/EC regulates the equipment and protective systems intended for use in potentially explosive atmospheres.

Directive 2004/37/EC on exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work (2004/37/EC) lays down minimum requirements for the protection of workers. Diesel exhaust gases and respirable crystalline silica are among the most widespread process-generated substances with a carcinogenic effect that workers at mines or quarries and adjacent processing plants may be exposed to.

Facts and figures

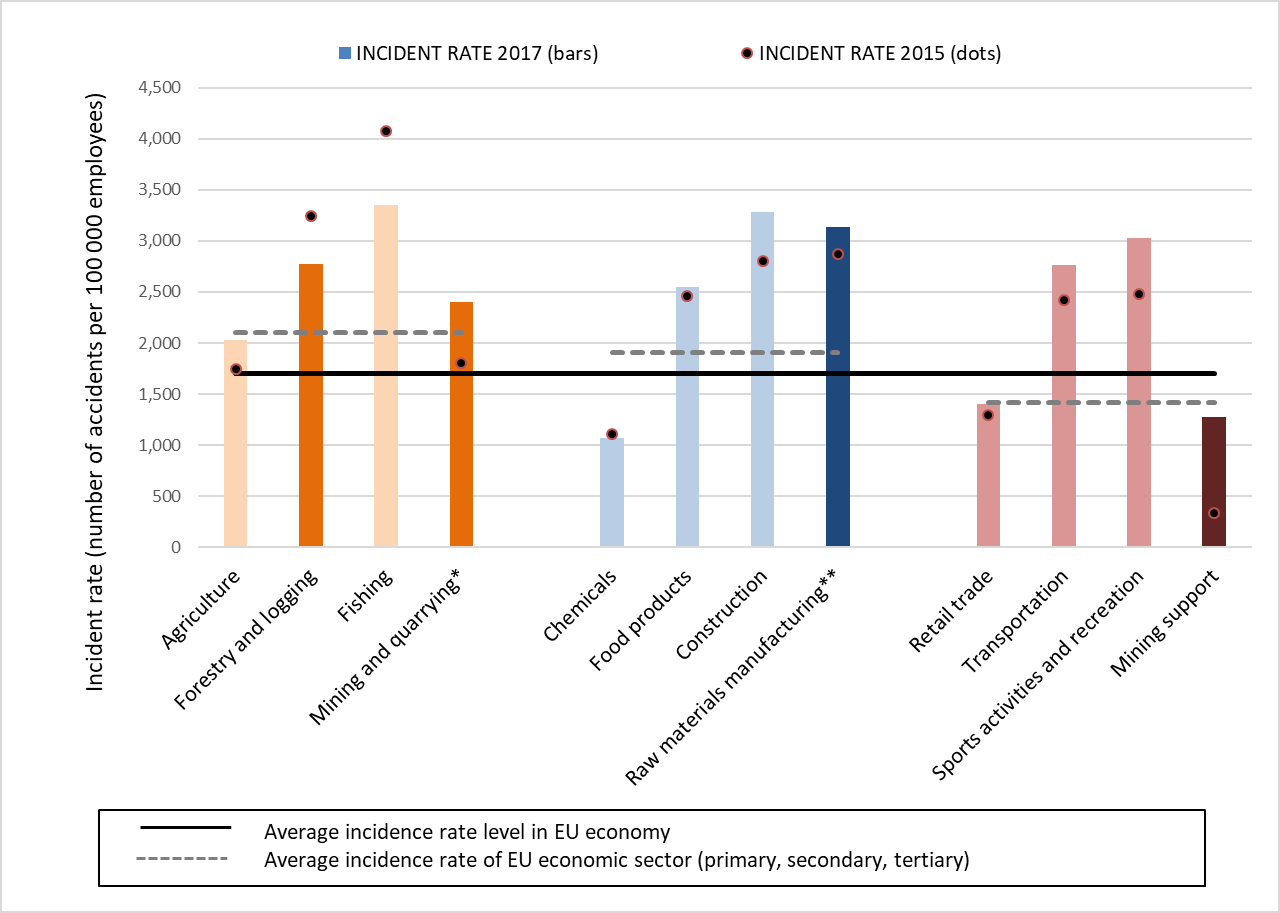

Figure 1 shows the incidence rate for non-fatal accidents[1] occurring at the working place in raw materials and other economic activities in the different sectors of the economy, i.e. for extractive activities (primary sector), basic manufacturing (secondary sector) and service activities (tertiary sector). For comparability purposes, the average incidence rate level in the whole EU economy and incidence rates of each of the three economic sectors are also shown.

The figure suggests that the raw materials sector is relatively exposed to hazards leading to non-fatal accidents, similarly to other high-risk sectors such as fishing, construction or sports and recreation activities.

*Oil and gas extraction activities excluded. ** Average of a selection of non-food, non-energy raw materials manufacturing activities.

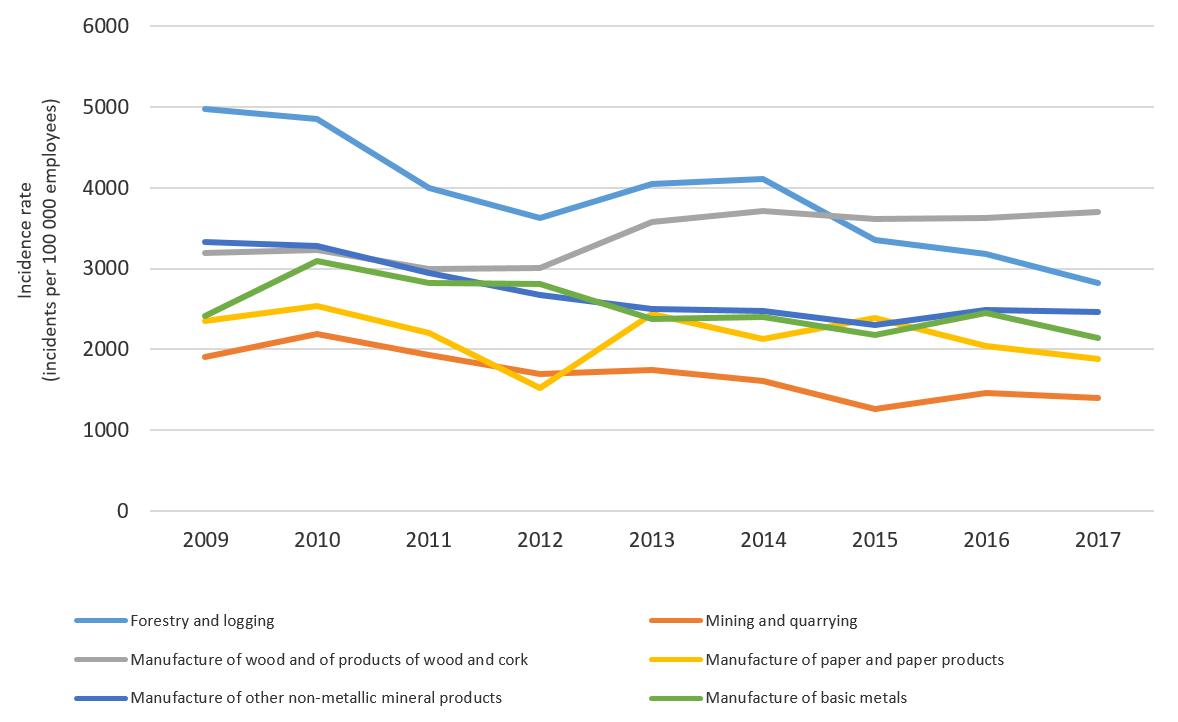

Figure 2 presents the 2010-2017 trend for the incidence rate of non-fatal accidents for selected raw materials industries. From 2015 (the last year monitored in the edition of the 2018 Scoreboard), the trend was almost stable for the manufacture of basic metals (-1%) and the manufacture of wood (2%). Mining and other non-metallic minerals sector had a slight increase in the incidence rate in the same period (12% and 6%, respectively). A decreasing trend is instead observable for the paper manufacturing sector (-20%) and for forestry and logging (-18%). Considering the period 2010-2017, the incidence rate of non-fatal accidents decreased respectively by 43 and 27%in these two sectors.

Conclusions

Raw material activities have relatively high rates of non-fatal accidents, with rates at the same level as other high-risk sectors such as fishing or construction. The current EU policy and regulatory framework strongly encourages establishing preventive and protective measures to improve health and safety at work. Regular reporting on rates of incidence of accidents and the understanding of the causes of accidents will help to achieve a continuing improvement in health and safety at work in the raw materials industry, which is an essential component of the sector’s social sustainability.

References

European Commission, 2008, ‘Causes and circumstances of accidents at work in the EU’, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities.

[1] Non-fatal accidents are accidents that result in more than three days’ absence from work without fatal consequences.

[2] Source: EC - European Commission. Raw materials Scoreboard. European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials. Luxembourg; 2016.

[3] Primary sector: agriculture (NACE A01), forestry and logging (A02), fishing (A03) and mining and quarrying (B07 and B08). Secondary sector: manufacture of chemicals (C20), manufacture of food products (C10), construction, raw materials manufacture (C16 and C23-C25). Tertiary sector: retail trade (G47), transportation and storage (H), sport activities and recreation (R93) and mining support service activities (B09). Incidence rate of Mining and quarrying was obtained as the weighted average of Mining of metal ores (B07) and Other mining and quarrying (B08). Incidence rate of (manufacture of) Raw materials was obtained as the weighted average of Manufacture of basic metals (NACE C24), fabricated metals (C25), other non-metallic mineral products (C23) and wood and wood products (C16). Weights in both cases reflects the number of employees of each activity.

[4] Average incidence rate of all economic activities displayed as cross-sectors line. Average of primary activities corresponds to Agriculture, forestry and fishing (NACE A); and secondary activities corresponds to Manufacturing (C). Average of the services sector, due to data limitations, is the weighted average of NACE activities G-J and L-N.

Overview and context

The social sustainability of mining operations and other activities and installations in relation to the different subsectors of the raw material value chain is closely related to the local and, where appropriate, regional community involvement and participation in the decisions that will affect them (World Bank and IFC, 2002).

The concept of ‘Social Licence to Operate’ (SLO) refers to a local community’s acceptance or approval of a project or a company’s ongoing presence, beyond formal regulatory permitting processes (e.g. public hearing and rights for written interventions). SLO derives from the acknowledgement that stakeholders may threaten a company’s legitimacy and ability to operate through boycotts, picketing or legal actions.

From a company perspective, obtaining a SLO is essential for reducing the risk of public criticism, social conflict and damage to the company reputation, which could reduce its profitability.

A formal and agreed definition of SLO is not yet available. The term has been adopted by a wide range of actors in the resources sector, including mining companies, civil society and NGOs, research institutions, governments and consultants. The concept of SLO relates not only to mining, but also to other industries, including pulp and paper manufacturing (Gunningham et al., 2004), alternative energy generation (Hall et al., 2013), nuclear energy, and agriculture (Williams et al., 2011).

The mining sector was one of the themes reviewed during the 19th session of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development. In this context, it was stressed that efforts are needed to maximise the positive economic impacts of mining in producing countries. It was also recommended that local communities should be integrated in decision-making processes and that the rights and interests of indigenous peoples are recognised and respected by states and companies (United Nations, 2012 A/RES/66/288 - The Future We Want).

Influencing factors

Different aspects can influence the social licence, for example demands and expectations, legitimacy, credibility and trust, and consent (Parsons et al., 2014). In recent years, substantial research has been conducted to understand public attitudes towards mining and the factors contributing to the SLO (e.g. Litmanen et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015).

Some studies highlight that, to obtain a SLO, mining companies have to develop good relations with all the stakeholders; legitimacy, credibility and trust are the main components necessary to achieve SLO (Moffat and Zhang, 2014). Such trust is affected by the extent to which a mining company manages and mitigates operational impacts and the way companies engage with communities and treat community members.

Browne et al. (2011) and Prno (2013) highlight the importance of both the social and the environmental context; establishing good relationships with the community, transparency and information disclosure, good and open communication, public participation and stakeholders' involvement are seen as crucial for achieving SLO. Mining companies should also be sensitive to cultural norms, create realistic expectations, develop fair conflict resolution mechanisms, be consistent and predictable regarding their ethical behaviour and try to accommodate the needs of the community.

Measuring SLO

According to Eurobarometer,in the EU, public acceptance of the extractive industries is low, compared with other economic sectors, while trust in mining companies is generally higher in countries outside the EU.

The Environmental Justice Atlas documents and catalogues social conflicts related to claims against perceived negative social or environmental impacts due to different extractive activities. The frequency and intensity of these conflicts might be used as a proxy for measuring the level of acceptance of the sector.

However, owing to its intangible nature, quantitatively measuring and modelling SLO is particularly challenging and has been contested (Moffat et al., 2016). In order to understand the drivers of social acceptance and derive measures and benchmarks, some large-scale surveys of citizen attitudes have been conducted in the mining context.

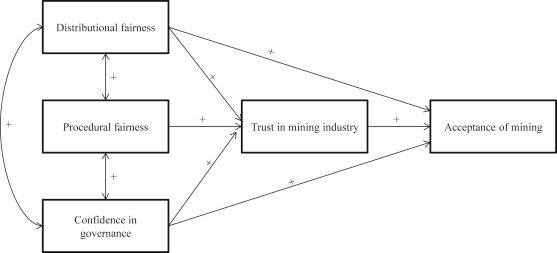

A path model developed by Zhang et al. (2015) highlighted the importance of trust in the mining industry and identified the stronger predictors of trust in local communities, for example procedural fairness, distributional fairness and confidence in governance (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Model of the social licence to operate. Zhang et al., 2015, ‘Understanding the social licence to operate of mining at the national scale: a comparative study of Australia, China and Chile’, Journal of Cleaner Production Vol. 108, pp. 1063–1072.

The Thomson and Boutilier model (2011) identifies four factors constituting the Social License: economic legitimacy, socio-political legitimacy, interactional trust and institutionalised trust. These factors were used to develop a pool of statements intended to measure the SLO in interviews with mine stakeholders, identifying their level of agreement/disagreement with such statements.

The social dimension of Circular Economy

As stated in the new Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) a more circular economy (CE) has positive effects in terms of reduced environmental impacts and resources use. Moreover, consumers will benefit from more durable and safe products, trustworthy and relevant information on products and protection against green washing and premature obsolescence.

CE can also have a positive net effect on job creation, if workers acquire the skills required by the green transition.

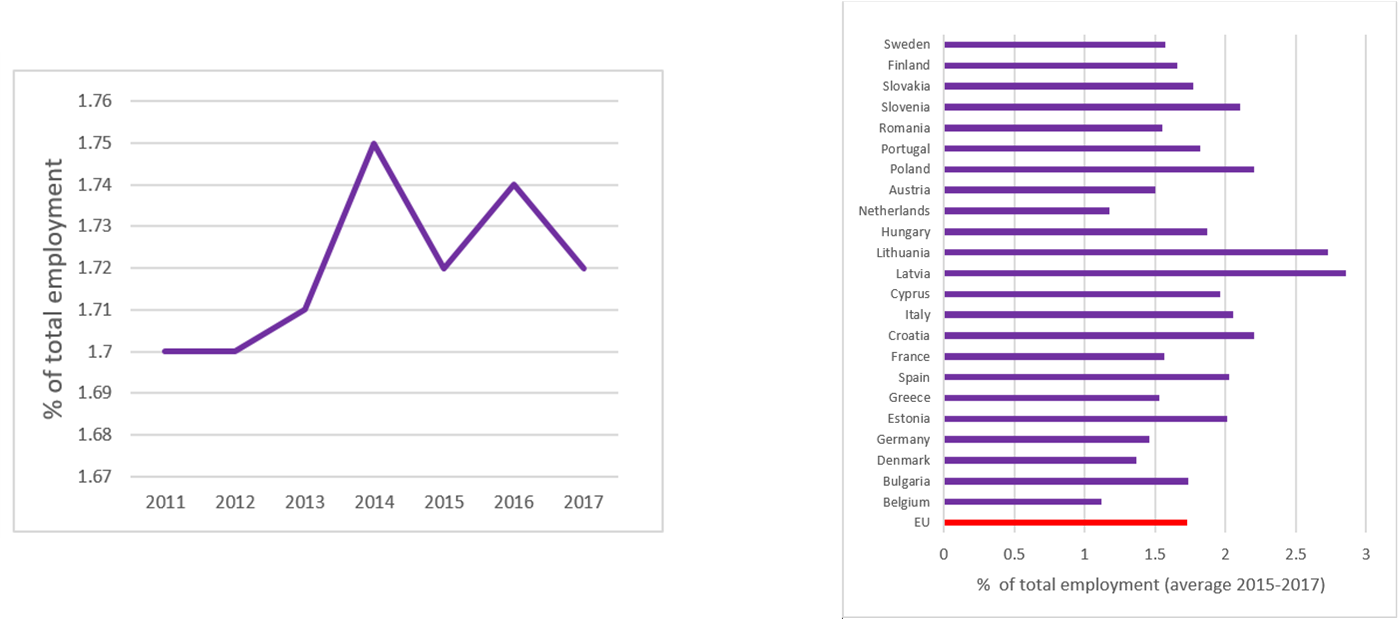

According to the Monitoring Framework for the Circular Economy, the total number of person employed in circular economy related activities in the EU were almost 4 million in 2018. The percentage of persons employed in these sectors over total employment have been growing in the last years and ranges from 1.1 to 2.8% in the various member states (Figure 1).

Sectors affected by the transitions to circular economy

According to projections published in a study by Cambridge Economics, moving towards a more circular economy could bring to a net increase of 700k jobs by 2030. However, the sectoral composition will change, and sectors producing primary raw materials will decline in size, while the recycling and repairing sectors will experience additional growth.

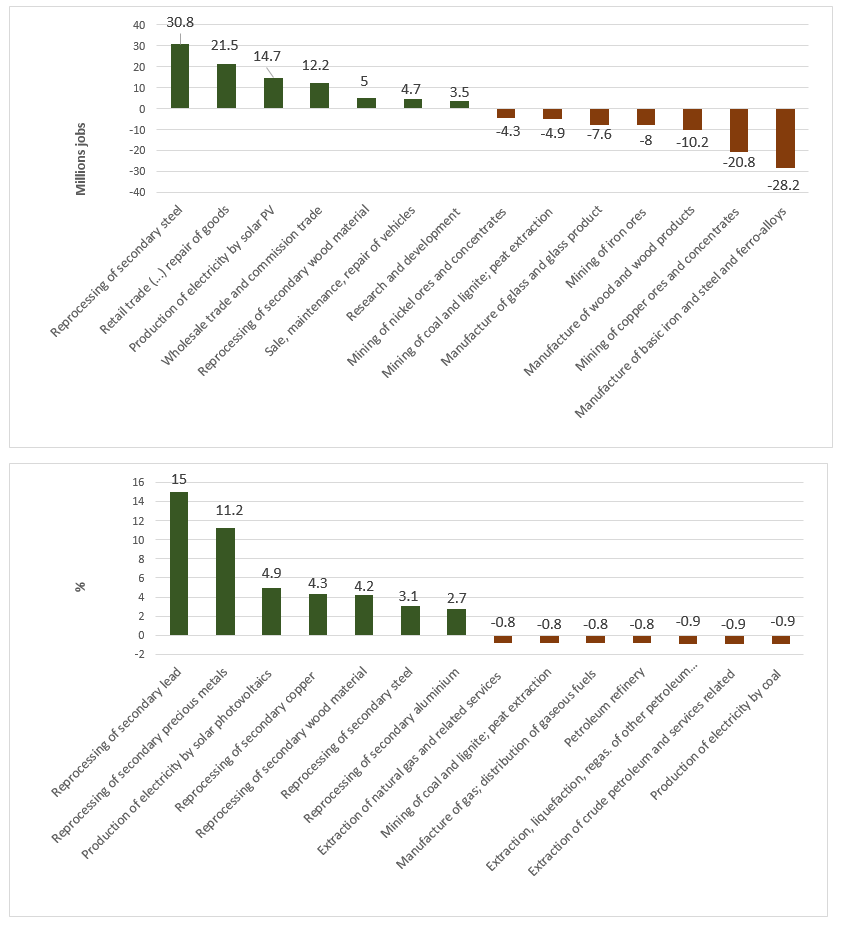

Similarly, according to a study from ILO (International Labour Organization), the sectors experiencing the highest job demand growth under a circular economy scenario would be the reprocessing of metals (e.g. lead, copper, precious metals), reprocessing of steel and wood materials. Manufacturing of basic iron and steel, manufacturing of wood and glass, mining of copper, iron ores and coals are instead the

Skills requirements

The circular economy will require new skills, including sorting, identifying the value and recognizing the hazards of different types of waste.

A report of the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP) and ILO reviews the current national regulations supporting employment and skills development in the transition to greener and more circular economies. The report analyses policies and initiatives in six countries and account for the different ways of defining and estimating green skills.

Waste classification and management is one of the identified skill gaps related to circular economy identified in national programs, for instance in Spain and UK.

Waste management and informal economy

Waste management and recycling sector employ a significant number of persons in certain developing countries and in the context of an informal economy. According to the ILO report “Greening with jobs” this activity employs 500k people in Brazil, more than 62k in South Africa and from 400 to 500k people in Bangladesh.

Informal waste workers include informal street sweepers, household waste-collectors, helpers to the municipal collection crew, and waste-pickers in the streets and on the landfills who collect, process, transport and trade waste alongside workers from the public and private sector (Wilson et al 2012; Medina 2000).

Several studies show that informal waste-picking is well integrated into the recycling value chain, as the recycling industry is reliant on a range of formal and informal components (Guibrunet 2019). Formal recycling industries’ main input (recyclable materials) comes in great amount from informal waste-picking (Chi et al., 2011, Streicher-Porte et al., 2005, Wilson et al., 2009).

As in the case of Artisanal and Small Scale Mining, given the informal nature of this phenomenon, it is particularly challenging to have accurate and updated global estimates on the number of people occupied by this activity.

Numerous studies report serious challenges in this sector in terms of occupational hazards and exposure to toxic substances, which affects both workers and local communities, especially in the case of e-waste management.

Given its important role (e.g. in reducing landfill volumes and providing livelihood for a relevant number of people), efforts for the formalization of this sector and the improvement of working conditions are undergoing in many countries. For instance organization of cooperatives and other types of social and solidarity economy organizations (ILO, 2014).

The program Sustainable Recycling Industries (SRI) aims at building capacity for the sustainable integration and participation of small and medium enterprises from developing and transition countries in the global recycling of secondary resources. Funded by the Swiss State Secretariat of Economic Affairs (SECO) and is implemented by the Institute for Materials Science & Technology (Empa), the World Resources Forum (WRF) and Ecoinvent, it has projects involving the informal sector in Colombia, Egypt, Ghana, India, Peru, and South Africa.

[1] The economic activities considered as part of the circular economy includes activities related to recycling and repair and reuse.